|

Richard Oakes

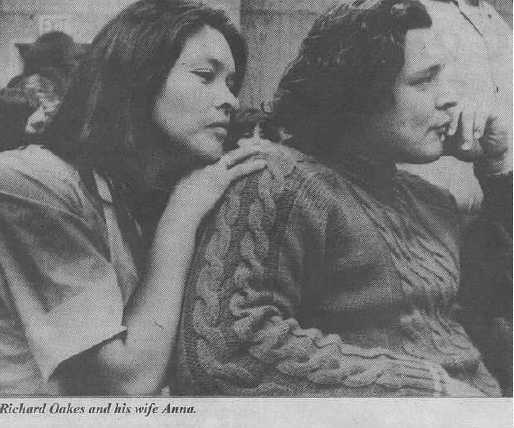

A Spark that Ignited Native American Self-Determination: by Bill Sullivan On the morning of November 9, 1969, a beautifully restored three-master schooner bearing the name Monte Cristo set sail from Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco Bay and steered course toward Alcatraz Island, the abandoned federal prison. On board were a number of Native American students from San Francisco State University, as well as a group of urban Indians from the Bay area. They had come to reclaim a piece of their land by right of discovery. The Indians brought a drum, and spectators cheered and waved as the Bay area resounded with high-pitched melodies of ancient people many thought to be extinct. The ship’s captain had agreed only to circle the island in a symbolic gesture, but a 28-year old Mohawk from New York had other ideas. When the ship came within two hundred-fifty yards, Richard Oakes threw off his shirt and plunged into the frigid waters and began to swim frantically toward Alcatraz. Spurred on by Oakes bold move, four others followed and they all made it safely to the island’s shore. Within an hour, the Coast Guard had returned them to Pier 39, but now they knew it could be done, and they would be back. Eleven days later, November 20, a group of approximately eighty Native Americans again landed on Alcatraz, and this time, they stayed. Richard Oakes leap into San Francisco Bay propelled him into a national spotlight. He was handsome, charismatic, articulate, and a natural leader. He became the face of the new Native American. An invisible race, who once owned this land, now captured the world’s attention. Native Americans from across the country journeyed to Alcatraz. Since many different tribes were represented, the name “Indians of All Tribes” was adopted for the group. They demanded nothing less than clear title to Alcatraz and developed elaborate plans to build a Native University, a cultural center, and a museum. An official with the General Services Administration--the government agency responsible for maintaining transitional federal properties--made plans to have U.S. Marshals remove the Indians by force, but the plan was called off when they realized the world seemed to support the Indian occupation. With race riots and Viet Nam protests at an all-time high, bloodshed on Alcatraz was the last thing the government wanted Americans to see on the news. The plight of Native Americans was the focus of numerous newspaper, television, and magazine pieces, and Oakes was sought out as the spokesman for this newly-emerging Native American movement. A former iron worker, he had only recently arrived in San Francisco after traveling cross country from the east. Along the way, he had visited a number of reservations and discovered firsthand the deplorable poverty and mistreatment of his Native American brothers and sisters. In February of 1969, Oakes enrolled as a student at San Francisco State and worked as a bartender in the Mission District of San Francisco. As a student, he soon became disillusioned with the courses offered for white students, so he worked with an Anthropology professor to form one of the country’s first Native American Studies programs. The program he founded is still being taught at San Francisco State today and he was recently honored with a room named after him. His work as a bartender brought him into contact with the area’s Indian community. The Mission District was inhabited by Native Americans who had settled there when they were forced off their reservations by the government’s misguided termination and relocation policies, which were programs designed to end Native American self-determination and to assimilate them into white society. The occupation of Alcatraz became the catalyst that turned public sympathy against assimilation and moved Indian policy toward self-determination and sovereignty for the indigenous people of this land. The occupation of Alcatraz lasted nineteen months, but Richard Oakes left the island following the tragic death of his thirteen-year old daughter, Yvonne, who fell three stories down a stairwell on January 5, 1970. Although saddened by Yvonne’s death, Oakes maintained his focus on the issues of his people. Alcatraz was only a beginning. Soon he was involved with the Pit River Indians in their struggle to regain 3.5 million acres of land stolen from them and being used by Pacific Gas & Electric. He also had dreams of buying a bus and creating a “mobile college for Native Americans”. But his dreams were cut short when he was shot to death under mysterious circumstances by the caretaker of a Y.M.C.A. camp in Sonoma County on September 20, 1972. Richard Oakes death was the spark that ignited the “Trail of Broken Treaties”, a coast-to-coast caravan to Washington, D.C. that culminated in the takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a siege that, once again, focused the nation’s attention on the needs of the first Americans. Hank Adams, one of the primary organizers of the march upon Washington wrote, “Richard Oakes presence beyond Alcatraz and his influence upon many Indian people shall continue to live within the body and soul of Indian experience. Born to the American soil, and responding strongly to his people’s struggle and suffering upon it, the living spirit of Richard Oakes could not now die nor cease to be remembered upon Indian land. Neither elegy nor eulogy can satisfy his life or death.” More about Richard Oakes |